Understanding Central Pain Syndrome (CPS)

After a stroke, the road to recovery is typically a long one, often determined by the severity of the stroke and the area of the brain where it occurred. When the brain’s blood flow and oxygen are blocked by a clot or broken vessel, a person’s speech, movement or memory may be affected. This damage may also interfere with the pain pathways of the central nervous system, complicating the recovery process. When that pain becomes chronic, it often falls under the broad umbrella of central pain syndrome (CPS), and can leave the person frustrated, depressed and yearning for relief.

What is Central Pain Syndrome?

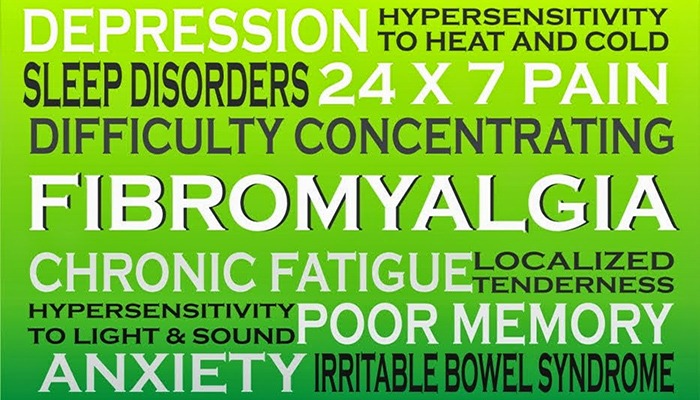

CPS is a neurological condition that may also be referred to as thalamic pain syndrome, Dejerine-Roussy syndrome, posterior thalamic syndrome, retrolenticular syndrome or central post-stroke syndrome, depending on the area of the central nervous system that has been affected. CPS can result from conditions other than stroke, including multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, tumors, trauma to the brain or spinal cord, limb amputations or Parkinson’s disease. Because it’s difficult to identify which condition is causing the pain, patients often go from doctor to doctor before receiving an accurate diagnosis. To complicate things further, symptoms may change over time, or occur off and on, deepening the mystery of the condition.

According to the National Stroke Association, approximately 10 percent of stroke sufferers later experience some form of pain. It may follow the attack immediately or begin months later, affecting the joints, face, arms, legs, hands, feet, torso or any combination of these areas. For some, pain comes in the form of burning, itching or a cutting or tearing sensation. For others, it may consist of sharp stabbing pains, dull throbbing aches, numbness or a “pins and needles” feeling on the skin’s surface. “

The term central pain syndrome can be a little confusing,” says Reginald Kapteyn, MD, a physiatrist, pain specialist and medical director of the Pain Relief Center at Drake Center, a division of University Hospital in Cincinnati. “What most individuals with CPS experience are nonspecific pain complaints over a large portion of their body, maybe in their torso, an arm or leg, or all of one side of the body. It is a lesion (or damage to the circuits) of the central nervous system’s deep neurological pathways that causes these symptoms in the periphery of the body. Although the symptom may be in the leg or arm, the condition is called central pain syndrome because the actual cause of the pain is coming from a central damaged circuit.”

Pain signaled from a damaged area of the central nervous system is different than traditional pain, Dr. Kapteyn says.

“This is not a traditional pain situation. With traditional pain, if you break your arm, you obviously are going to have significant pain and it’s appropriate pain,” says Dr. Kapteyn. “It’s the body’s own protective mechanism. We have wonderful medicines to treat that. In the case of CPS, however, this pain is not an appropriate signal. It’s an inappropriate signal because of a broken circuit, making the nerves more excitable. We have central sensitization and hyperexcitability of the affected nerves, so a very low level of stimulus will stimulate those pathways and cause pain or other sensations.

Diagnosing and Describing the Pain

Although there is no specific test for central pain syndrome, neurologists often make the diagnosis by stimulating the affected areas through touch and measuring the patient’s response, Dr. Kapteyn says.

“We’ll order tests to see if a person has nerve damage in the area that hurts, and if they don’t, we start to think it may be more central,” he continues. “We rule out other possible diagnoses and conclude that we may have a central phenomenon. The history of the pain is incredibly important, including where it is, whether it’s patchy or on an entire side, and whether the area of the person’s stroke corresponds to the area of pain. If they’ve had a left-sided stroke, do they have symptoms on the right side of the body? From there, we try sensory examination modalities. We can test for those symptoms with light touch and stimulate all the pathways that may be affected, or with cold or heat, or a pin prick. Loss of sensation or numbness is also sometimes a finding with these patients.”

Dr. Kapteyn explains that one hallmark of neuropathic pain is allodynia, when a sensation that is not normally painful becomes painful.

“If you brush the person’s skin with your hand, instead of feeling a light touch, they may feel as if needles are touching the skin,” he explains. “That sensation still sends a signal to the brain, but because the circuits aren’t working normally, a touch may trigger even more pain. The pain pathways are not regulated the way they used to be.”

For this reason, something as routine as getting dressed can become challenging.

“Putting on clothing can be extremely painful, and it’s something we struggle with during rehabilitation. The simplest thing, like putting your shirt on, buttoning buttons or shaking someone’s hand causes pain,” Dr. Kapteyn says.

Living with CPS

Ten years ago, Kyle Kountz woke up in the middle of the night with excruciating pain along his left side. Immediately he feared that he was having a heart attack. After running several tests, emergency room physicians ruled out heart trouble but couldn’t determine the cause of his pain.

Kountz, then a manager at an RV dealership, continued experiencing pain on the left side of his head, neck and chest, along with pain in his left arm and leg. At times, it was so debilitating that he’d lie on the office floor for hours, waiting for it to subside. His primary care physician scheduled a treadmill stress test that also ruled out a heart condition. Later, a neurologist conducted a brain scan and discovered three right-side lesions, indicating Kountz might have had several mini-strokes.

“My pain has progressively gotten worse over the years,” Kountz says. “About eight years ago, it got so bad that I had to quit working. I really hate not being able to work, because I loved my job. But I would have these spells of severe pain, and I just couldn’t function.”

Like many with chronic pain, Kountz’s journey to an accurate diagnosis of central pain syndrome was frustrating.

“I went to a couple of neurologists, and they basically told me that I wasn’t in pain, but I knew better,” he says. “I always felt like they doubted me. I could check my blood pressure when I was in pain, and it would be really high. But when I wasn’t in pain, it was always low. I don’t even remember how many MRIs I’ve had. At one point, they thought I might have multiple sclerosis, but I didn’t, and I even had two spinal taps, which didn’t show anything.” For six years, Kountz took methadone. Recently, his pain management specialist helped him transition to Nucynta (tapeutadol), a prescription analgesic.

Avoiding Pain Triggers

Some people with central pain syndrome are able to identify situations that bring on or worsen their pain, which can help them manage their symptoms better.

“Environmental changes like extreme cold or heat, the sun shining on your skin or even decreased sleep, which alters brain chemistry somewhat, may be triggers,” Dr. Kapteyn says. “Even sudden movement can trigger pain at times, like if someone is in a car driving down a bumpy road.”

But some people, like Kountz, do not notice any specific triggers.

“There’s really nothing I can do to aggravate my pain or to lessen it. I went to a gym for a while and worked out really hard, but it had no effect on the pain. Heat doesn’t bother me, either, so sometimes I’ll take a hot bath, and it may help a little, but my pain is almost constant,” Kountz says.

As with many medical conditions, stress can also make pain worse. “Stress is intimately linked, in part because it ramps up your nervous system and sensitizes it,” Dr. Kapteyn says. “When you’ve got a rapid heart rate or you’re sweating, your nerves are primed to feel sensory input. If you have a syndrome like this, you’re going to feel things more. It’s important to adopt behavioral coping mechanisms to decrease that ramping up of the nerves, and to be mindful of how you are feeling at any given moment. Meditative techniques can be helpful. Guided imagery is another wonderful technique designed to deregulate, or calm down, any stressors or excitability in the nervous system.”

“My pain has progressively gotten worse over the years,” Kountz says. “About eight years ago, it got so bad that I had to quit working. I loved my job. But I would have these spells of severe pain, and I just couldn’t function.”

Balanced CPS Treatments

Because the pain signals associated with central pain syndrome differ in nature from those associated with traditional pain, NSAIDs, opioids and other pain medicines are not the typically prescribed treatment, Dr. Kapteyn says. Tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsant or antiseizure medicines often provide good results.

“The standard treatment is to use medications that calm the nervous system, and drugs like NSAIDs and opiates are not considered to be the first line here,” says Dr. Kapteyn. “If you determine that there’s an underlying neuropathic phenomenon, you immediately use a blend of medicines we call ‘balanced analgesia,’ where a combination of medications targets the specific pathways that are giving pain signals. Antidepressants that modulate norepinephrine are good, because they make your body’s own pain-blocking mechanisms work better. Opiates typically do not cause a good response, because they work by blocking a pain pathway that is working normally. Ibuprofen is a prostaglandin inhibitor which reduces inflammation, so it typically will not help a neuropathic pain syndrome like this, because there’s no inflammation involved. This treatment must be tailored to the underlying neuropathic diagnosis. We may use Neurontin (gabapentin), which actually decreases neurotransmitter release in the brain. Antiseizure drugs such as Trileptal (oxcarbazepine), Depakote (valproic acid), Lyrica (pregabalin) and Topamax (topiramate) have also proved beneficial.”

Neurologist Seth Stoller, MD, director of cancer pain management for Overlook Hospital’s Department of Neuroscience in Summit, New Jersey, agrees.

“CPS patients have a hyperexcitability state, where an area of the brain that should be functioning normally becomes revved up, with no brake, and it’s going full-throttle,” Dr. Stoller explains. “As a result, the body perceives pain because the brain is not firing the way that it should. When that’s happening, you want to alleviate the pain by slowing some of those pathways down. Antidepressants, specifically the tricyclics, and anticonvulsants are often effective, because they help the brainwaves flow better. We try to avoid narcotics and opioids because of a phenomenon called central sensitization that can actually exacerbate the pain in some cases.

Baclofen, a medication for spastic-movement disorders, is sometimes effective, Dr. Stoller says, as are other nondrug therapies including massage, stretching and, for some patients, acupuncture.

The Future of CPS

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), which is part of the National Institutes of Health, is at the forefront of research being conducted on CPS in stroke patients. Learning more about the neurological consequences of damage to the central nervous system from stroke and its potential treatments remains a major part of the organization’s focus.

“Some of the most interesting research is being done in the area of neuromodulation, where a low-level current of electricity is passed through the affected area, either resetting the brain in certain instances or decreasing the incorrect firing of those nerve impulses,” says Dr. Kapt eyn. This procedure is also referred to as deep brain stimulation.

Dr. Stoller adds, “There is some evidence that deep brain stimulation may help, and we’re hoping that may be on the frontier, although it’s not a standard of care at this point.”

Research into new and effective CPS medication is also promising. “We’ve really only begun to understand the pharmacologic benefits of some of these medicines in the last ten years, and especially in the last few years, much more than we used to,” says Dr. Kapteyn.

Although experts agree that CPS is still somewhat of a conundrum, they are optimistic when it comes to restoring their patients’ quality of life.

“Central pain syndrome is difficult to treat,” Dr. Kapteyn says. “We don’t just look at this as reducing a person’s pain level from a 7 to a 5 on a scale of 1 to 10. We work to decrease the intensity of the pain, but we also get more detailed by trying to decrease the frequency of specific symptoms such as burning, stinging or stabbing sensations. Although it is a chronic condition and we don’t yet have the modalities to reverse it, we do have the modalities to help alleviate the pain and allow patients to carry on with their lives.”

PainPathways Magazine

PainPathways is the first, only and ultimate pain magazine. First published in spring 2008, PainPathways is the culmination of the vision of Richard L. Rauck, MD, to provide a shared resource for people living with and caring for others in pain. This quarterly resource not only provides in-depth information on current treatments, therapies and research studies but also connects people who live with pain, both personally and professionally.

View All By PainPathways