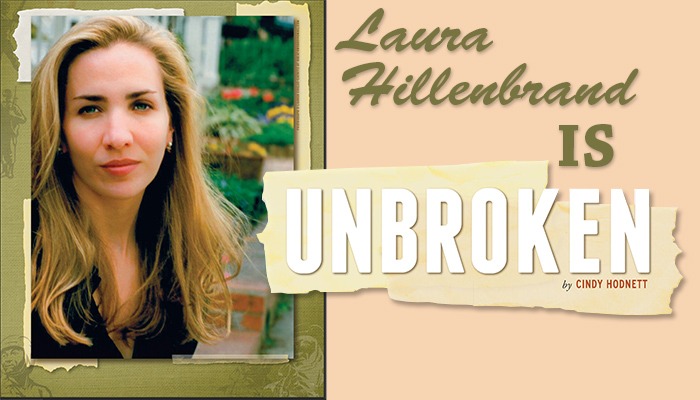

Laura Hillenbrand Confronts Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Best-selling author Laura Hillenbrand confronts chronic fatigue syndrome by writing stories that inspire.

People familiar with the agony and challenges of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or anyone who suffers from or cares for someone in chronic pain can identify with author Laura Hillenbrand. Dismissed by doctors and unable to find relief, the acclaimed author of Seabiscuit and unbroken has dealt with the same experiences and frustration as thousands of individuals seeking help for under-recognized illnesses. Though her struggle has continued for more than 25 years, she remains determined.

THE ONSET OF CHRONIC FATIGUES SYNDROME

“It was a nightmare,” Hillenbrand says of the onset of her CFS in 1987. “I don’t know how many doctors I went to back then, but I dealt with a great deal of condescension and derision. Blood tests aren’t definitive, and especially 25 years ago, people were told, ‘It’s all in your head.’ I had lost a lot of weight, so one doctor said that I must be anorexic or bulimic and even followed me to the bathroom and put his ear to the door to hear if I was throwing up.”

[pullquote]“It was a nightmare,” Hillenbrand says of the onset of her CFS in 1987.[/pullquote]The onset of Hillenbrand’s chronic fatigue syndrome was abrupt. In “A Sudden Illness,” an essay she wrote for The New Yorker, she describes her experience during a ride back to Kenyon College after spring break. Hillenbrand was traveling with her boyfriend, Borden, and friend Lincoln when the first symptoms struck. “I was about to speak when an intense wave of nausea surged through me,” she writes. “The smell from the bag on the floor was suddenly sickening. I wrapped my arms over my stomach and slid down in my seat. By the time we reached campus, half an hour later, I was doubled over, burning hot, and racked with chills. Borden called the campus paramedics. They hovered in the doorway, pronounced it food poisoning, and left.”

Hillenbrand’s physical condition continued to deteriorate. Eventually, her painful symptoms forced her to make a life-altering decision.

“In the next few days, everything I ate made my abdomen balloon,” she writes. “I radiated heat, and my joints and muscles felt bruised. Every day on the way to classes, I struggled a little harder to make it up the hill behind my apartment. Eventually, I began stopping halfway to rest against the trunk of a tree.

“One morning, I woke to find my limbs leaden. I tried to sit up but couldn’t. I lay in bed, listening to my apartment-mates move through their morning routines. It was two hours before I could stand. On the walk to the bathroom, I had to drag my shoulder along the wall to stay upright. Linc drove me to the campus physician, who ran test after test but couldn’t find the cause of my illness. After three weeks of being stranded in my room, I had no choice but to drop out of college.”

THE DIAGNOSIS OF CFS

[pullquote]“One morning, I woke to find my limbs leaden. I tried to sit up but couldn’t. I lay in bed, listening to my apartment-mates move through their morning routines. It was two hours before I could stand.[/pullquote]Like many with CFS, Hillenbrand found medical professionals to be skeptical and even contemptuous, which slowed her search for successful treatment. After dropping out of college and returning home, she continued to see new doctors until she finally found an answer at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

“My lymph nodes were enormous, and I had a fever and chills all the time. I was so weak that at times I was unable to speak,” Hillenbrand says. “I never bought the idea it was all in my head for a second; I knew I was desperately ill. Then Dr. John Bartlett, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins told me “The people who told you this was all in your head are wrong. This is a real disease, called chronic fatigue syndrome. We don’t know what causes it.’”

With her diagnosis, Hillenbrand had a name for her illness, but no treatment or cure. She says it was devastating to have a medical diagnosis that had no proven treatment options. “It’s easy to get demoralized, but you have to seek other answers,” says Hillenbrand. “You can’t ever give up.”

WRITING AS THERAPY

Hillenbrand’s spirit remained unbroken. Her never-give-up mentality eventually found its way into her writing. In 2001, she published a best seller, Seabiscuit: An American Legend, the story of a thoroughbred racehorse that captured America’s heart during the throes of the Great Depression. The book was made into an Academy Award-nominated film in 2003 and catapulted Hillenbrand into the national spotlight.

Following her success, Hillenbrand continued to battle CFS, suffering a severe relapse that left her so weak she was unable to leave her home for two years. When the relapse hit, she was two years into writing her second book, Unbroken, the unbelievable true story of Louis Zamperini, an Olympic runner whose dreams of breaking the four-minute mile were destroyed by a plane crash and subsequent torture in a Japanese war camp during World War II. As her health slowly improved, Hillenbrand was able to complete the book. Unbroken was released in 2010 and quickly became a #1 New York Times bestseller. A movie based on the book is now in development.

According to Hillenbrand, writing both books was therapeutic.

“I feel wonderful when I finish a book,” she says. “With both books, I wrote about individuals whose lives were full of motion, something I have been robbed of. In writing about them, I was able to climb out of my body and into theirs, and as I’ve written the books, I’ve felt the experiences along with them — the hardships and how they come out on the other side. I don’t think I’ll ever write a book about something downbeat.”

OPERATION INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN

The publication of Seabiscuit prompted a second huge development in Hillenbrand’s life. Along with the critical acclaim and financial success, the book served as a connection between the author and thousands of needy children in Iraq.

“In 2003, I received an email from an American lieutenant colonel who was touring Iraqi girls’ schools. He was struck by the terrible condition of the schools, and the fact that the children had virtually no school supplies — no books, few pencils, almost no paper. He carried a copy of Seabiscuit and told the story of the horse to the girls, who were enraptured. He sent me photographs of himself with the girls climbing all over him, holding my book and laughing. My book had just been translated into Arabic, and I resolved that day to try to get copies of it to Iraqi children.

“As I was resolving to try to help Iraqi children, [actor] Gary Sinise had also gone over with the USO, and he was so upset by the conditions that he wanted to start a school-supply drive,” Hillenbrand continues.“So we founded Operation Iraqi Children [which later became Operation International Children (OIC)]. Working through American troops, OIC distributes school supplies and other necessities to needy children in war-torn regions. We have reached hundreds of thousands of kids in Iraq, Afghanistan, the Philippines and Djibouti. We want to be wherever the American military is.”

THE ONGOING BATTLE WITH CFS

Twenty-five years after Hillenbrand’s diagnosis, the medical community has an increased awareness of chronic fatigue syndrome. However, despite medical research, an effective treatment remains elusive for many patients, including the celebrated author.

“I can’t make plans of any kind,” Hillenbrand says. “I work when I can work — when I feel good and the muses are singing to me. When I have a really bad day, I can’t do much at all. I listen to audio books and try to distract myself and wait for it to pass.

“CFS is very different for different people,” she says. “Generally, it ebbs and flows. Some people go for several days and you can’t tell that anything is wrong with them, and then they crash. And the reason they crash is because it is difficult to tell where the line is. If you push the line and overexert, you can fall down a cliff suddenly and relapse.”

Many factors, including autoimmune disease, viral infection and autonomic dysfunction, are being investigated as causes of chronic fatigue syndrome. Hillenbrand is hopeful that once a definitive cause is determined, research into a treatment will advance rapidly. However, until that happens, she plans to continue taking her life one day at a time, enjoying her literary success as well as the small victories of each day.

“To be honest, other than my husband, a lot of people I should have been able to count on let me down,” Hillenbrand says. “That’s a story a lot of people with CFS will tell. Along with derision from the medical community, they often didn’t get a lot of support from people close to them.

“My husband and I are both kind of cerebral people, so we talk a lot,” she continues. “I can’t travel, but we try to get out and take small adventures because just being together is our vacation. We might walk by the Potomac River and go to a café. I go to places where I can see beautiful things. Those are my best days.” For others who are battling health issues, Hillenbrand returns to a familiar theme: hope.

“If you are struggling with any form of chronic disease, do not lose hope about your life,” Hillenbrand says. “There are ways to make your life meaningful and happy. Everyone has to find their own way, but you can. And remember that what were once crippling disabilities are now curable. There is always hope.”

PainPathways Magazine

PainPathways is the first, only and ultimate pain magazine. First published in spring 2008, PainPathways is the culmination of the vision of Richard L. Rauck, MD, to provide a shared resource for people living with and caring for others in pain. This quarterly resource not only provides in-depth information on current treatments, therapies and research studies but also connects people who live with pain, both personally and professionally.

View All By PainPathways