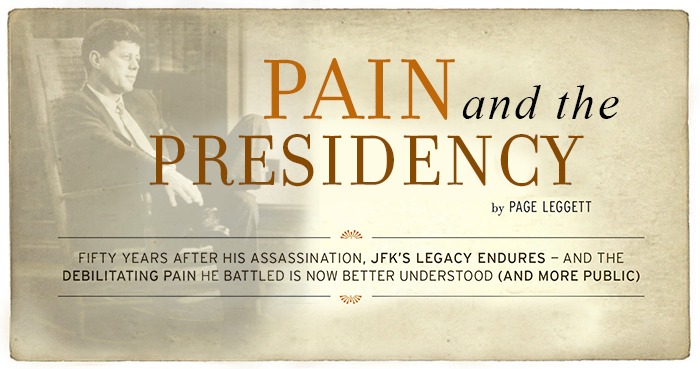

JFK and Chronic Pain

Nearly everyone has an opinion on what defines John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Some define him as a civil rights pioneer or the man who believed we could land on the moon. Others were drawn to Camelot, the refined cultural era he and his elegant wife, Jacqueline, ushered in. Conspiracy theorists may define the Kennedy era primarily by the day an assassin’s bullets ended his life.

However you view our 35th president, his brief presidency — only 1,000 days — has become legendary. Mythic, in fact. Although it had never waned, interest in JFK surged last year, as the nation and the world looked back on the 50th anniversary of his assassination and how that day shaped America.

Part of his legacy, we now know, is the ferocious pain he endured. His struggle with chronic back pain was a side of Kennedy few people saw.

While he went to great lengths to conceal it, his medical condition was well known to family, friends, and aides. It’s instructive now to look at how he dealt with the pain, how society viewed it, and what lessons we can learn from a president who refused to let pain limit him.

HE TRUTH

ABOUT JFK’S CHRONIC PAIN

Although the public could never have guessed it from JFK’s deep tan and rugged athleticism, he had been unwell for most of his life.

Kennedy’s full medical records were finally released to the public in November 2002. On November 18 of that year, Dr. Jeffrey Kelman, a Harvard-trained, board-certified physician with specialties in internal medicine, pulmonary medicine, and geriatrics, appeared on the PBS News Hour to discuss “President Kennedy’s Health Secrets.”

“John Kennedy was sick from age 13 on,” Dr. Kelman said. “In 1930, when he was 13, he developed abdominal pain. By 1940, his back started hurting him. By1944, he had his first back operation. By 1947, he was officially diagnosed [with] Addison’s disease.” In the meantime, his back pain was exacerbated by foot-ball injuries and a 1943 boat crash during his wartime service in the US Navy.

“He was basically sick… through the rest of his life,”Dr. Kelman continued. “He had two back operations, in 1954 and 1955, which failed. And he needed chronic pain medication from 1955throughhis White House years until he died. He was never healthy.… The images you get of vigor … wasn’t true. He was playing through pain most of the presidency.”

The public may have been aware of his potentially deadly Addison’s disease, but only after he was in the White House. Thomas H. Maugh, II, who writes about science and medicine for The Los Angeles Times, wrote in 2009, “President Kennedy’s Addison’s disease, which came to light only after his election in 1960, was most likely caused by a rare autoimmune disease.”

The disease, an adrenal deficiency, is more serious than Kennedy’s confidants let on. Dr. Kelman explains: “The adrenal gland makes … hormones used for salt metabolism and in response to stress and inflammation. In ’47, he was officially diagnosed … as being adrenally insufficient, and from that point on… he was being treated with daily corticosteroids…to survive.”

CONVENTIONAL

(AND UNCONVENTIONAL) TREATMENTS

Like many who suffer from chronic pain, President Kennedy was under pressure from family and staff to bravely keep his “game face” on, but his pain required daily treatment. Swimming in an indoor pool heated to a “therapeutic ninety degrees,” according to Bill O’Reilly in his 2012 bestseller, Killing Kennedy: The End of Camelot, was part of his regimen. But so were prescription drugs.

“By the time he was president, he was on 10, 12 medications a day,” Dr. Kelman maintains. “He was on antispasmodics for his bowel … muscle relaxants, phenobarbital, Librium, meprobamate … codeine, Demerol, methadone … oral cortisone; he was on injected cortisone, he was on testosterone, he was on Nembutal for sleep. And on top of that, he was getting injected sometimes six times a day, six places on his back, by the White House physician, with Novocain, procaine, just to enable him to face the day.”

The physician giving him those injections was the first woman to serve as White House physician. Janet Travell, MD, was known for her groundbreaking work on“trigger points.” In fact, she coined the term to describe pain points in muscles that radiate outwards and cause what is now known as referred pain. Her book Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual has been called a bible for pain specialists.

Kennedy — then a US senator from Massachusetts— was referred to Dr. Travell once he became so disabled that he took a seven-month leave from politics. Erin McCloskey indicates in a 2002 article for The International Journal of Applied Kinesiology and Kinesiologic Medicine,* “After receiving treatments from Dr. Travell, he was not only out of the wheelchair and off crutches but playing golf, football and tennis. Dr. Travell was able to locate muscular sources (trigger points) for his chronic pain and injected low-level procaine directly into the Senator’s lumbar muscles, which proved effective.”

Remarkably effective, according to James North, MD, an anesthesiologist and pain medicine specialist at Carolinas Pain Institute and assistant professor at Wake Forest Baptist Health. Dr. North says JFK’s active life was a testament to “what a multimodal approach to pain can do.”

Dr. Travell also used noninvasive treatments on her famous patient. McCloskey’s article and University of Virginia professor Larry Sabato, Ph.D.’s 2013 tome, The Kennedy Half-Century, both reveal Dr. Travell’s discovery that one of Kennedy’s legs was shorter than the other, which exacerbated his back pain. So she fashioned a heel lift for one of his shoes, which he wore throughout his presidency.

And in a historically significant gesture, she gave Kennedy a rocking chair like the one she had in her office. She believed a person in a rocking chair was subtly using his muscles as he gently rocked. The chair had a place in JFK’s Oval Office and eventually became known as the “Kennedy rocker.”

Much has been made over the iconic rocker, although the public hasn’t been widely aware that it was prescriptive. Bill O’Reilly writes about the “awkward way [Kennedy] eases himself into his favorite rocking chair for meetings to lessen the pain in his back.”

CHANGING ATTITUDES

NEW TREATMENTS FOR PAIN

We’ve come a long way from the days when candidate Kennedy had to hide his disability, says Paul Gileno, president of the U.S. Pain Foundation, an organization he founded in 2006. Gileno knows first hand about living with pain. “While I am proud to be the founder of a national pain organization, I consider myself a person with pain first,” he says.

We’ve also come a long way in terms of diagnosing conditions that lead to chronic pain. Improved imaging quality is one of the biggest advancements in the field, says Dr. North. In addition, he says, minimally invasive surgery — something JFK never had access to — is available today. So are neuropathic pain medications.“This is an entire class of drugs that weren’t around 50years ago,” Dr. North says. “A lot of Kennedy’s pain had become centralized and, therefore, more difficult to treat. Today’s neuropathic drugs may have helped.”

Gileno is a history buff who has read extensively on JFK’s chronic pain and how he kept it hidden. “It had to be hush-hush back then,” he says. “But in some ways, he was a role model for people living with pain today. I wish he’d been able to talk about it — to begin tearing down some of the barriers we face,” Gileno says.

Yes, President Kennedy suffered from debilitating pain and he took medicine for it, but he didn’t let it limit him. “If Kennedy can handle chronic pain while being president, maybe others living with pain and navigating their workplace today, with the additional resources we have today, will be inspired to carry on,” Gileno says.

Gileno advocates being upfront at work about chronic pain. “We want people to own it,” he says.“Don’t be ashamed. You may even have to educate your boss: ‘I have this diagnosis. Here are my limits, but here are all the things I can do.’”

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

In the 1950s and ’60s, Kennedy didn’t have the luxury of making his condition public.

As we know now, the public and the private Kennedy were two different people. He didn’t let on in public that he was in pain, but his family and aides knew the truth — and worked to suppress it.

In 2002 The New York Times wrote about a biography Robert Dallek was writing called An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963.** Dallek examined JFK’s medical records with Dr. Kelman. As The Times reported, “The new information shows how far Kennedy went to conceal his ailments and shatters the image he projected as the most vigorous of men. It is a remarkable example of a phenomenon that has been seen many times, notably in the case of Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

Addison’s was debilitating. (“Kennedy collapsed twice because of the disease,” Maugh writes.) But it was far from the only condition causing JFK pain. As Dr. Kelman reported on PBS about what the then-newly-re-leased X-rays revealed, “He had compression fractures in his low back; he had osteoporosis. In 1954, they put a plate in because the pain was so bad he needed — or they felt he needed — to have his spine stabilized. It got infected in ’55, [and] they took the plate out. By the late ’50s, there were periods he couldn’t put his own shoes on because he couldn’t bend forward.”

Kennedy worried that the steroids he took to treat Addison’s disease caused a puffy face and made him look overweight. Steroids classically cause what is known as a “moon face.”

According to Robert Dallek in his book An Unfinished Life: JFK 1917–1963, four days before his inauguration Kennedy caught sight of himself in a mirror and declared, “My God, look at that fat face. If I don’t lose five pounds this week we might have to call off the inauguration.” Several photographs of Kennedy, like the one here, have this appearance.

NOVEMBER, 22, 1963

BRACING FOR PAIN

Kennedy used a brace to stabilize his back. He was wearing one on November 22, 1963, and some have argued that he could have survived the assassination attempt had he left the brace at home. “The back brace he is wearing holds his body erect,” writes O’Reilly in Killing Kennedy. “The president fortified its rigidity this morning by wrapping the brace and his thighs in a thick layer of Ace bandages. ”

It may have been a history-altering decision.

Says Sabato, “No one had even considered that the president’s back brace, needed to stabilize his war-injured torso, would make it difficult for him to duck or be pushed down in the limo in the event of an attack.”

According to O’Reilly, “If not for the brace, the [second] bullet, less than five seconds [after the first], would have traveled over his head.”

LESSONS

FROM A PAINFUL LEGACY

The lessons people take from Kennedy’s hidden pain are as diverse as opinions on the man and his presidency.

Sabato argues in The Kennedy Half-Century that keeping his condition — and the “mind-distorting drugs” he was on — secret amounted to “deception of the public.” He calls it the “underbelly of JFK’s legacy.”

But Dr. Kelman reached a different conclusion after examining JFK’s medical records. “You can make a timeline at the Kennedy Library looking at day by day, sometimes hour by hour, the history of [his] presidency. And in correlating it as well as you could with the medical records, [pain] didn’t seem to have affected his presidency at all. His judgment wasn’t warped, in spite of the fact that he seemed to be in pain a great deal of the time. It didn’t affect his performance as president. In certain ways, I came out of it thinking he was a heroic character.

”Kennedy, Dr. Kelman said, “was living with a disability which probably would get him federal disability or retirement if he was around today. He was on enough pain medications to disable him. And he survived … and performed at the highest level.”

O’Reilly praises Kennedy’s pushing through the pain.“A less driven man would have taken to bed long ago,” he writes, “but John Kennedy refuses to let his constant pain and suffering interfere with … his duties.

”Biographer Dallek concluded, according to The New York Times: “[F]or all of Kennedy’s suffering, the ailments did not incapacitate him. In fact, … while Kennedy sometimes complained of grogginess, detailed transcripts of tape-recorded conversations during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 and other times show the president as lucid and in firm command.”

Dr. North credits Kennedy’s positive outlook, coupled with innovative medical care, with his ability to persevere. “He ran the world’s most powerful nation in spite f the pain,” he says. “It shows how powerful the mind can be, in combination with good physician care.”

Kennedy “led a very purposeful life,” Dr. North continues. “He didn’t let the pain consume him. Staying busy and active, as he obviously did, is a very therapeutic way to manage pain.”

Regardless of politics, Gileno views the way the president handled his pain as inspiring. John F. Kennedy didn’t allow it to limit him or his aspirations. He refused to let pain be his entire story. Gileno lives the same way. He says, “I encourage people to adopt an attitude of, ‘I live with chronic pain, but it doesn’t define me.’” {PP}

*McCloskey, Erin.“Her Spirit and Work Live On.” The International Journal of Applied Kinesiology and Kinesiologic Medicine (ISSUE NO. 13, SPRING 2002).

**Altman, Lawrence K. and Todd S. Purdum. “In J.F.K. File, Hidden Illness, Pain and Pills.” The New York Times. NOVEMBER 16,2002.

PainPathways Magazine

PainPathways is the first, only and ultimate pain magazine. First published in spring 2008, PainPathways is the culmination of the vision of Richard L. Rauck, MD, to provide a shared resource for people living with and caring for others in pain. This quarterly resource not only provides in-depth information on current treatments, therapies and research studies but also connects people who live with pain, both personally and professionally.

View All By PainPathways