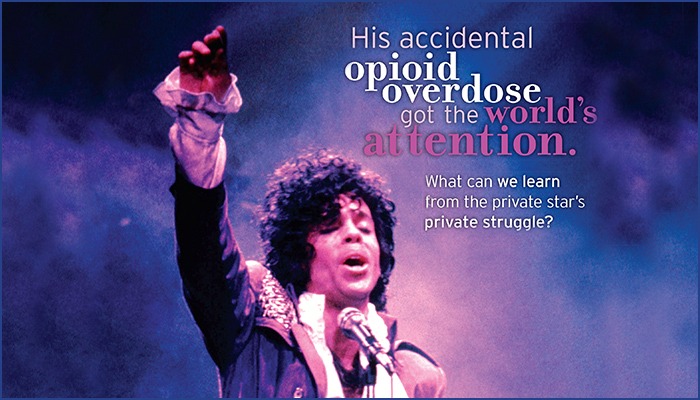

Prince

Prince, who died in April at age 57, sang openly about emotional anguish—and about sex, religion, race, and nearly every other challenging topic. But despite that openness in his music, Prince kept his own excruciating pain private.

His death from an accidental fentanyl overdose devastated millions of fans. From some celebrities, an overdose wouldn’t have come as a surprise, but Prince—an active performer, Jehovah’s Witness, and staple of his hometown community who eschewed cigarettes and alcohol—wasn’t one of them.

Any of us who live with pain and has ever put on a brave face for family, friends, bosses and coworkers will relate to the desire—the need, even—to not let on about what ails us. Admitting to being in chronic pain can often lead to being labeled as flawed, even being a responsibility shirker. It can mean a lessening of value in the workplace and the home front—or worse. On top of all this, in Prince’s case, it probably meant insurers would be reluctant to guarantee he’d show up for work.

Penney Cowan, founder of the American Chronic Pain Association, says she and her organization coach people living with pain to listen to their bodies and slow down when pain creeps in. “Prince probably didn’t have that ability,” she says. “As a performer, if you don’t show up, you may not get booked again. And if Prince didn’t show up—or didn’t give a performance his all—the whole world would’ve known.

Prince couldn’t be flawed,” Cowan says of society’s insistence that our heroes always be atop the pedestal we’ve placed them on. “That would’ve been a deal breaker.” The bottom line is, as a society, we’ve got to go easier on each other. And on ourselves.

Richard Rauck, MD, past president of the World Institute of Pain and director of the pain management fellowship at the Carolinas Pain Institute, says Prince’s death demonstrates that no one gets a pass when it comes to chronic pain: “No social, economic or cultural group is immune,” he says. “These distinctions spare no one.”

Neither does addiction. “Addiction can affect the rich and famous as well as the poor and downtrodden,” says Dr. Rauck, who “respected Prince as a musician” and feels grateful he got to see him in concert.

PRINCE’S PAIN A VICIOUS CYCLE

Prince Rogers Nelson’s death reminds us of the vicious cycle through which chronic pain can take its victims. The songwriter/entertainer was known for delivering high-energy shows. He didn’t just stand up and sing—which on its own can be exhausting. No: he jumped, he twirled, he pirouetted, he did splits in the air. When he was on tour, he maintained a grueling travel schedule. A Prince concert was a spectacle, and mostly because His Purple Highness was doing all the heavy lifting. But it took a toll on him—particularly his hips.

“I’ve never seen an artist of his age—or any artist—perform the way Prince did. I can only image how much worse his pain was after each show. I saw him about four years ago when it was known that he suffered from hip injuries, but you couldn’t tell from the high-energy performance he delivered that night,” says Dr. Rauck.

The more of himself Prince gave on stage, the more pain he felt. And, presumably, the more pain he felt, the greater the need for something to fix it. The public Prince was the guitar virtuoso, a songwriting genius, a Grammy-winning artist who had the audacity to make a movie (starring him!) and see it become an instant hit and ultimately a cult classic. The private Prince had a secret he couldn’t share.

“We all have limits,” Cowan says. Pushing through the pain only leads to … more pain. And possibly a greater dependence on painkillers.

OPIOIDS: THE WONDER & THE DANGER

Opioids—and fast-acting fentanyl is one—are a very effective class of drug, Dr. Rauck says. “There’s been a lot of media attention paid to them since Prince’s death, but it would be a mistake to use his death as a reason to presume all opioid use is bad.” It’s not.

But it is incumbent upon physicians who prescribe opioids to watch their patients closely for signs of possible addiction, and to intervene if necessary. Family members and friends should monitor the behavior of a loved one on opioids. Dr. Rauck suggests looking for signs of mood or behavior changes, drowsiness, frequent constipation, erratic behavior. Any of these can be signs of addiction.

Dr. Rauck adds, “One of the life-saving lessons for caregivers and people with pain is learning from this tragedy that an overdose can be reversed using naloxone. Have it on hand and know how and when to use it. If you haven’t already, talk to your family and your doctor.”

Prince’s death has elevated the national conversation about chronic pain and opioid use and abuse. Dr. Rauck believes part of that conversation has got to focus on finding a balance between “the public health epidemic” of opioid abuse and treating the large number of patients who benefit from the safe use of opioids.

At the same time, he adds, physicians (and people with pain) have to acknowledge that opioids are just one response to acute and chronic pain—not the only response. “There are always alternatives, options. It’s never just opioids and nothing else,” says Dr. Rauck. He lists a few of the alternatives or auxiliary treatments: physical therapy, acupuncture, meditation, anti-depressants, anti-inflammatories.

When a physician and patient agree that opioids are worth trying, Dr. Rauck says doctors should always try the minimal effective dose first. His advice is: “Be respectful of any drug.”

SHAME & STIGMA

Penney Cowan agrees. Her organization, ACPA, offers many resources to help people with pain and their families find the combination of treatments that will work best for them.

“When we first started the American Chronic Pain Association, we wanted to hire a celebrity spokesperson,” says Ms. Cowan. After all, as one of Christopher Reeve’s doctors said shortly after the late actor became a quadriplegic: “Diseases need icons.”

The public learned a lot about Alzheimer’s through University of Tennessee “Lady Vols” Coach Pat Summitt’s brave choice to be open about her battle with the debilitating illness. Similarly, ALS is so closely associated with the beloved Yankees player who died from it, the disease is commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

“But when we talked to PR people, they all said ‘No way’ when we asked if a celebrity client would align himself with chronic pain,” she says. “There’s too much of a stigma. People are afraid to be branded as unreliable and won’t work again. As a society, we expect 100 percent of people, all the time.”

Which brings us back to Prince. His fans adored him. He adored the adulation. Think of the photos of Prince in sparkling get-ups and full make-up, standing on stage and cupping his hand behind his ear. Asking the audience to cheer louder. The more we cheered, the more he gave. Until he gave out.

Cowan often talks about the importance of a support system. Any person’s chronic pain impacts his or her spouse, children, friends, boss and colleagues. The condition requires understanding on the part of the social network supporting the person living with pain. It may occasionally require tough love. If we see a loved one growing dependent on painkillers, we’ve got to speak up.

Prince—or anyone with fame and fortune—may find themselves surrounded by “yes men” (and women) reluctant to intervene. Those people may have even been unaware of his suffering. “Even someone of his stature—larger than life—may not have had a good support system,” says Dr. Rauck. “Prince may not have had anyone who’d tell him ‘no,’ and I’m sure he felt the pressure of maintaining appearances, keeping his pain private to protect everyone who worked with him. I’m sure most people in pain can relate.”

WHAT WE CAN LEARN

Cowan hopes Prince’s death will lead to a change in the national conversation. She says there are a few things she wants people to know and discuss:

- You can only have {one quarterback} on your team. Always work through your primary care provider.

- Opioids are only {one tool}. Consider all the tools available to you, and use them in combination with one another, if advised. “There are risks and benefits to every drug, “Cowan says.

- Use {one pharmacy} for every prescription you fill and every drug you’re on. That includes vitamins, over-the-counter meds and herbal supplements. If you get a discount on some meds through a mail-order pharmacy, let your local pharmacist know what you’re ordering by mail.

The death of Prince (the artist who sang “I Would Die 4 U”) was as a devastating blow because it seems to have been entirely preventable. But Prince is far from the first icon to be secretly addicted. Dr. Rauck mentions Heath Ledger’s death from an accidental overdose. Rush Limbaugh was also addicted to opioids, but sought treatment before it was too late.

Cowan hopes something positive can come from such a great loss: “I hope we can begin to erase some of the stigma. And I hope we can begin to acknowledge that we all have limits.” {PP}

PainPathways Magazine

PainPathways is the first, only and ultimate pain magazine. First published in spring 2008, PainPathways is the culmination of the vision of Richard L. Rauck, MD, to provide a shared resource for people living with and caring for others in pain. This quarterly resource not only provides in-depth information on current treatments, therapies and research studies but also connects people who live with pain, both personally and professionally.

View All By PainPathways