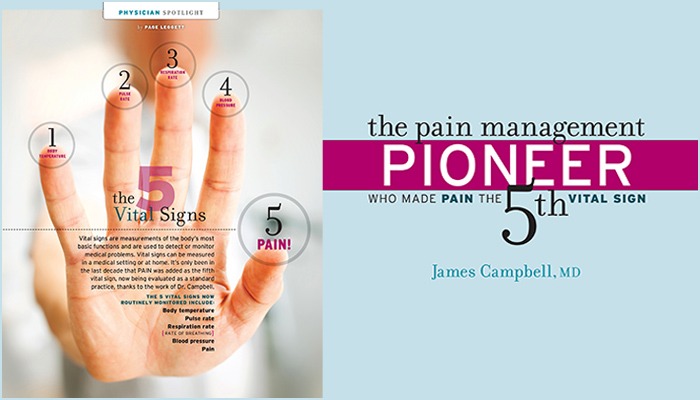

James Campbell, MD

Vital signs are measurements of the body’s most basic functions and are used to detect or monitor medical problems. Vital signs can be measured in a medical setting or at home. It’s only been in the last decade that PAIN was added as the fifth vital sign, now being evaluated as a standard practice, thanks to the work of Dr. Campbell.

THE 5 VITAL SIGNS NOW ROUTINELY MONITORED INCLUDE:

- Body temperature

- Pulse rate

- Respiration rate {RATE OF BREATHING}

- Blood pressure

- Pain

James Campbell, MD, HADN’T PLANNED TO GO INTO PAIN MEDICINE.

It was China that got Dr. James Campbell, founder of the Johns Hopkins Blaustein Pain Treatment Center, to start thinking about pain medicine.

He was in Yale Medical School in the 1970s when China began opening up to the West and found himself fascinated by news reports about acupuncture being used to control pain. While he didn’t want to study or practice acupuncture himself, he was interested in the concept that this ancient practice might have an impact on people in pain. It made him curious about what other pain treatments were out there—both those already in use elsewhere in the world and those yet to be discovered.

Dr. Campbell wanted to impact the ways people found pain relief, but he didn’t know at the time he’d go on to found and lead one of the largest pain research centers in the country. And though pain management was relatively new at the time, his choice to enter this discipline allowed him to impact more people than just about any field he could have chosen. According to the American Academy of Pain Medicine, chronic pain affects more than 100 million Americans—more than the combined number of Americans living with diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke and cancer.

Even if you haven’t heard of Dr. Campbell, a giant in the field of pain medicine, you probably know his work. While at Johns Hopkins University and president of the American Pain Society, he established the concept of pain as the “fifth vital sign.” The term became an entire promotional campaign for the field of pain management, and physicians nationwide now use the idea in their practices to balance out care. It’s become as important a barometer of a patient’s physical state as heart rate and blood pressure.

BIG {BETTER} CHANGES IN PAIN MANAGEMENT

CANCER, POST-OP, ANATOMY, GENETICS & MORE

Years ago, Dr. Campbell says, people with cancer died fairly early in the course of the disease. Over his long career, he’s seen people live much longer after a cancer diagnosis. It’s good news, but it also means their pain may last longer—and needs to be managed longer and more effectively. Once science began to prolong the lives of cancer patients, it became time to examine quality of life.

“Scientific advancements mean people aren’t struck down by cancer as quickly as they once were,” he says. “But the pain that arises from both cancer and its treatment can become chronic. And that needed to be addressed.”

That new understanding—that people could live with cancer for years before succumbing to it—led to the now-familiar and much-loved hospice movement, Dr. Campbell says.

He has also seen significant changes in doctors’ concerns about post-op pain. “There was very little sensitivity to that” early in his career, Dr. Campbell says. “Neuropathic pain wasn’t even a concept 20 years ago.”

Another fascinating insight realized during his career: Pain has little to do with anatomy. Not so long ago, doctors thought the two were closely linked.

Mild arthritis can lead to extreme pain, and severe arthritis can lead to very minor pain, he points out. “An anatomical snapshot doesn’t tell us what a person feels.” We now know genetics play a key role in how people perceive pain, Dr. Campbell says. He gives a hypothetical example of Mr. Jones, who has arthritis and complains of back pain, and Mr. Smith, who has arthritis but doesn’t seem to have pain. “Is Mr. Jones just making it up?” he asks. “No. W c studies in rats and mice that show some genetic strains of a disease lead to lots of pain behaviors, while others—in the same dis-ease—show no signs.

“There are individual differences,” he continues. “This is not just bad luck or all in your head.” That’s good news for patients, who used to have to convince some physicians their pain was real.

“Attitudes are influenced by our understanding of the underlying disease,” Dr. Campbell says. Again, he illustrates with an example. Diabetic patients in the mid-1990s presented with burning pain in their feet. “It sounds neurological, not orthopedic,” he says. “But the neurological exam came back normal. So, doctors thought: patients are making this up. It’s psychological.”

But then doctors did biopsies, looked under a microscope and discovered “profound pathology.” Doctors immediately understood the importance of small-fiber neuropathies as a cause of burning pain in the feet. Overnight, attitudes changed once doctors were faced with evidence that this pain was real. “We can’t observe pain,” Dr. Campbell says. “What we can do is listen and have empathy. We can tell our patients: ‘I believe you. I understand you have a cant problem, and I want to help.’ Many patients thank me for just believing them.”

Dr. Campbell adds, “In some cases, patients can learn to cope with their pain better through changes in cognitive styles. Pain does not always mean that there is a serious underlying disorder. Learning to adapt to disease and pain can sometimes lead to a better quality of life. Coping skills can be learned, and may enable patients to move forward and have productive lives without necessarily having to take drugs.” He says the outlook for pain medicine is bright. “In the future, there will be better physiological markers. Brain imaging will help us.”

Part of treating a patient has to do with doctors’ attitudes. Dr. Campbell believes doctors have come a long way—but not far enough. “Decades ago, the prevailing outlook was that chronic pain wasn’t taken all that seriously,” he says. “There’s still an element of that today.”

SAFE USE OF OPIOIDS

{EDUCATION IS IMPERITIVE}

You can’t talk to one of the founders of pain medicine without asking about opioids. “They’re a very tricky class of drugs—but also an amazing class of drugs,” Dr. Campbell says. “They have the potential to be dangerous. So patients on opioids must be followed closely.”

Many people who use them have an initial positive response. But here’s the rub: they then need increased doses to achieve the desired effect, and that leads to dependency.

“We’ve got to educate health care practitioners on how to use, when to use, how to monitor patients and how to be safe,” he advises. The answer isn’t to stop prescribing opioids. It’s to understand their risks, discuss those risks with patients, prescribe conservatively and monitor extremely closely.

Lots of patients benefit from opioids used carefully, he says. A small percentage—maybe 10 percent—might develop an addiction. This is, he says, a societal problem.

In fact, Dr. Campbell points out that pain is a problem across our society. Pain costs at least $560 billion annually, which accounts for the total incremental cost of health care due to pain and the cost of lost productivity (based on days of work missed, hours of work lost and lower wages). Dr. Campbell has advocated for the safe use of opioids for some time. In 2007 Congress stating: “People who endure chronic, unrelieved pain are more likely to suffer depression and anxiety. They have trouble sleeping, have other physical ailments and take longer to recover from these ailments. They lose time at work, lose caring for children and other dependents, and suffer deteriorated relationships with family and friends.

“I have treated thousands of patients who suffer with severe significant pain. Some of them say, ‘Enough is enough’ and ultimately give up because of the chronic pain. Some of this is due simply to the problem of under treatment.”

Dr. Campbell understands the plight of the patient in pain, and at the same time is also aware of patients self-medicating. “Doctors, at times, unintentionally contribute to the problem by writing prescriptions for opioids ill-advisedly or for too many pills for conditions such as post-operative pain,” he says.

Both doctors and patients—and their friends and families—need to be aware of the danger. Prescribe carefully, he advises. Monitor closely. Understand the risks.

And always be open to new ideas and approaches—even if that “new” idea is a centuries-old practice. After all, it was Chinese acupuncture that first made Dr. Campbell curious about the world of available treatments. {PP}

PainPathways Magazine

PainPathways is the first, only and ultimate pain magazine. First published in spring 2008, PainPathways is the culmination of the vision of Richard L. Rauck, MD, to provide a shared resource for people living with and caring for others in pain. This quarterly resource not only provides in-depth information on current treatments, therapies and research studies but also connects people who live with pain, both personally and professionally.

View All By PainPathways