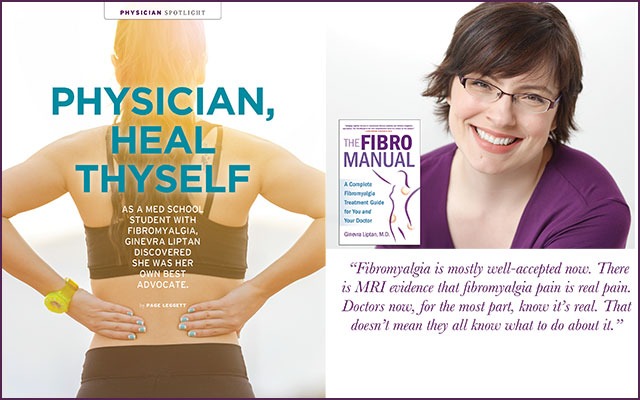

Ginevra Liptan, MD, and her fibromyalgia book

As a med school student with fibromyalgia, Ginevra Liptan discovered she was her own best advocate.

Ginevra Liptan, MD, had never heard of fibromyalgia when she began feeling overwhelming fatigue. It was 1999, and she was a typical medical student, working insane hours and experiencing extreme stress. She chalked up her tiredness to the pressures of preparing to become a doctor.

But then came the pain. It started in her neck but eventually went from her scalp to her toes. “Everything hurt,” says Dr. Liptan, whose first name is pronounced Jen-EV-rah.

And what compounded the pain into anxiety and frustration was that every doctor she visited told her she was fine. Beginning with her primary care physician, who ordered lab work and declared Dr. Liptan “OK,” and then on to a series of specialists who ran their own tests that came back “normal,” the entire medical establishment—including a top rheumatologist—kept telling her, “You’re fine.”

Except she wasn’t. Her body was telling her what doctors refused to acknowledge.

Ultimately, it wasn’t even an MD who diagnosed her. “It was my neighborhood chiropractor who finally knew what was wrong with me,” says Dr. Liptan.

“Fibromy-what?” she asked him.

“I felt failed by medicine,” she says. “I wondered why I was even studying medicine.”

She was too exhausted to return to Tufts University School of Medicine and knew she couldn’t keep up with the rigors of being a third-year medical student when future physicians are expected to work 80 to 100 hours a week as they do their rotations. She took a year off, but she found she couldn’t even keep up with the babysitting gig she had. “I just felt flattered,” she recalls. “When I would take a shower and try to wash my hair, my arms were too weak to lift to my head.”

The time away wasn’t relaxing or restorative. “That was my darkest time,” Dr. Liptan says. “I was miserable and alone.”

But she didn’t wallow in that for long. She had to help herself. “I realized: I have a mission,” she says.

She switched to an anti-inflammatory diet, cut out dairy, ate more protein, got more (and better quality) sleep, and—perhaps the most important aspect in her path back to wellness—began myofascial release (MFR) massage. “That was the first thing to give me real benefit,” she says.

She estimates that this combination of treatments and lifestyle changes led to a 60 percent improvement in her pain and fatigue. It was enough to allow her to return to school. And the long and frustrating journey, with all its false starts and dead ends, left no doubt about what sort of medicine she should practice.

Today, Dr. Liptan estimates she’s seen an 80 percent improvement over when she was at her lowest. “I feel so much better now,” she says. “I still have some pain and fatigue, but I’m strict with self-care. I take my diet, stress relief, and sleep schedule seriously. It’s what I teach my patients, too.”

Stretch Goals

Dr. Liptan searched for years for a diagnosis and stumbled her way to treatments that worked for her. What she discovered is that the fascia, the connective tissue that attaches, stabilizes, and separates muscles and internal organs, is key to understanding and treating fibromyalgia. She has written, “The massive connective tissue network that surrounds all of our muscles—think of the shiny outer coating on a raw chicken breast—plays a huge role in chronic musculoskeletal pain like fibromyalgia and chronic low back pain. Medical understanding is behind … but is catching up with the … emerging field of fascia studies, starting with the first Fascia Research Congress, held at Harvard in 2007.”

She describes the fascia as the “armor of the body, tightening immediately in response to signals from the many nerves running throughout it.

“Researchers believe that a rapid contraction of the fascia is what creates the enormous extra strength that humans can produce in emergencies,” she continues.

“With fibromyalgia, we know that the brain is mistakenly triggering the danger or ‘fight-or-flight’ alarm bells all the time, instead of only in emergencies,” says Dr. Liptan. “This occurs not in our thinking brain, but in those areas that control housekeeping functions like breathing and digestion. Sustained danger signals from the brain to the muscles result in chronically tight muscles.”

So, treatments that can get painful knots out of the muscles and surrounding fascia are often effective in treating fibromyalgia. MFR involves a combination of sustained manual traction and prolonged gentle stretching of fascia.

Two recent studies in Europe found that after 20 sessions of MFR, fibromyalgia patients reported significant pain reduction. What’s more, the relief is long-lasting. Most people reported reduced pain levels even six months after their last session. “Can you imagine if a drug did that?” Dr. Liptan asks. “If this were a drug study, it would have been all over the news.”

Dr. Liptan recommends patients try at least two to three MFR sessions to determine if it’s beneficial for them. While it can temporarily cause increased muscle soreness—the kind you might feel after intense exercise—a day or two later, the muscle pain is usually better than prior to the session. Those who find it helpful should go for therapy once or twice a week for about eight weeks—a typical schedule for any physical therapy regimen. After that, patients can go for a “tune-up” as needed.

While no treatment—including MFR—will work for everyone, Dr. Liptan says that between 80 and 90 percent of those who try MFR get relief from it.

Be certain your massage therapist is trained in MFR. It’s most likely you’ll find an MFR practitioner in a doctor’s office. (You’re not likely to find one at a day spa.) It can be expensive, and insurance companies balk at covering it. If you have trouble finding an MFR practitioner, look for a DO—doctor of osteopathic medicine. They’re fully licensed physicians who emphasize a whole-person approach to health and wellness.

In addition to MFR, Rolfing™ is a manual therapy that can be effective. A form of hands-on manipulation developed more than 50 years ago, Rolfing focuses on the fascia around the joints, with treatment emphasizing correcting posture and joint alignment in a series of 10 to 12 sessions.

Some physicians perform the osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT), a combination of gentle stretching and pressure on the muscles and joints. Unlike the other effective treatments, this one is generally covered by insurance. Physicians can also perform trigger point injections to break up painful muscle knots.

Help Yourself

Fortunately, there are techniques you can use on your own to treat painful fascia. At the Frida Center for Fibromyalgia, which Dr. Liptan founded in Portland, Oregon, self-care is a primary focus. Dr. Liptan recommends patients place a small, soft ball under any tight and painful areas of muscle. “Allow yourself to sink onto the ball for a few minutes to provide the right amount of sustained pressure to allow the fascia to release,” she explains.

Yin yoga—often called restorative yoga—provides relief for many fibromyalgia patients. The slow, gentle form of yoga includes supported stretching with props such as pillows and bolsters that help you settle into a comfortable pose you’ll hold for three to five minutes. It’s a relaxing practice that benefits the mind and body.

Dr. Liptan had to find many of these techniques herself when she first began her journey 18 years ago. Doctors, including her medical school professors, were dismissive of her symptoms. She had no one to serve as a mentor or resource. “There was a lot of trial and error involved,” she says of her search for relief. “I was stumbling around on my own and wondering, ‘Do I have to be my own doctor?’ It was so discouraging.

“Most doctors back then didn’t feel fibromyalgia was a ‘real’ disease,” she continues. “It wasn’t even an official diagnosis. Even today, there can still be a dismissive attitude and the thought that this is just a ‘hysterical woman’s disease.’”

But that’s changing. “Fibromyalgia is mostly well-accepted now,” Dr. Liptan says. “There is MRI evidence that fibromyalgia pain is a real pain. Doctors now, for the most part, know it’s real. That doesn’t mean they all know what to do about it.”

After Dr. Liptan had figured out her own diagnosis, her own trusted primary care physician admitted she had suspected fibromyalgia might be the culprit. But the doctor told her: “I didn’t want to give you that label or stigma.” Dr. Liptan countered: “Shouldn’t you have let that be my decision?”

Dr. Liptan found herself in an unusual position. She knew more than her doctors did about her condition. She says many fibromyalgia patients today know what that feels like. They have to educate their physicians on the disease.

Spreading the Word

Since Dr. Liptan can’t reach every fibromyalgia patient and every physician from her Portland clinic, she decided to write a book. “I can’t be the fibromyalgia doctor for all of America,” she says. “There are 10 million Americans living with the condition.”

In 2016 she published The FibroManual: A Complete Fibromyalgia Treatment Guide for You and Your Doctor. The book provides a way for—and she knows this seems backward—patients to educate their doctors. Dr. Liptan counsels her fellow fibromyalgia sufferers: “It’s unfortunate, but you will have to know more than your doctor about your condition.”

That’s the scenario she’s living now. “Even today, I don’t have a doctor who treats my fibromyalgia,” she says. “There are lots of us in this unenviable position. No one should have to be their own doctor.”

In her book, Dr. Liptain recommends four simple steps—Rest, Repair, Rebalance and Reduce—in treating the disease. Simply put, those include:

- Restoring deep, restful sleep

- Achieving long-lasting pain relief

- Optimizing hormone and energy balance

- Reducing fatigue

Dr. Liptan is able to help many—even most—patients she sees. “The people who tend to get better are those with the ability to make changes in their life,” she says. “They’re the people who have access to care, including massage therapists; can afford supplements; can get a CPAP machine, if needed; and can make dietary changes.”

But she can’t work miracles. “I tell people that 20 percent of their improvement will come from what we do in the office—but 80 percent comes from what they do at home.”

Still, speaking to a doctor who understands their pain has a therapeutic benefit on its own. “Patients tell me they feel better emotionally after talking to me,” she says. “They feel heard and believed—and there’s real healing in that.”

PainPathways Magazine

PainPathways is the first, only and ultimate pain magazine. First published in spring 2008, PainPathways is the culmination of the vision of Richard L. Rauck, MD, to provide a shared resource for people living with and caring for others in pain. This quarterly resource not only provides in-depth information on current treatments, therapies and research studies but also connects people who live with pain, both personally and professionally.

View All By PainPathways