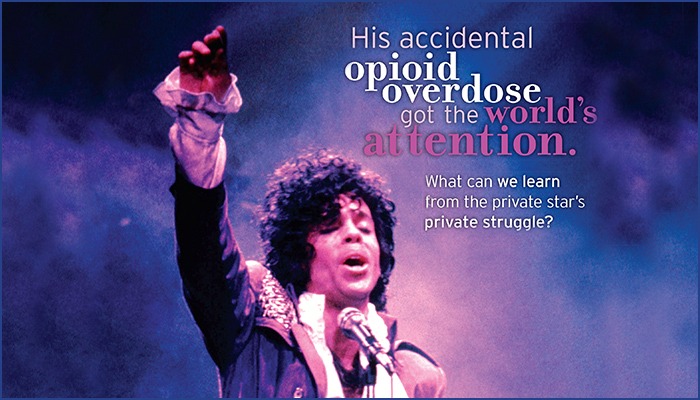

Opioid Overview

The number of Americans who suffer from chronic pain is staggering. It’s around 50-100 million, says Jeff Gudin, MD, the director of Pain Management and Palliative Care at Englewood Hospital and Medical Center in New Jersey.

That’s the equivalent of all the people in California and Texas—and a few other states thrown in—who live with chronic pain.

“Decades ago, there weren’t a lot of highly effective treatment options,” says Dr. Gudin, who is also a clinical instructor of anesthesiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai University. “There were millions of people who did not get relief from available treatments.”

CLEARLY, SOMETHING HAD TO BE DONE ABOUT THE PAIN EPIDEMIC.

Enter opioid analgesics—a class of powerful medications (including codeine, morphine, oxycodone and fentanyl, with brand names OxyContin, Duragesic, Dilaudid and Vicodin) that provide effective relief in appropriate patients, but were prescribed with what now seems like alarming frequency. The pain epidemic rolled into a prescription painkiller epidemic. Since 1999, the amount of prescription painkillers prescribed and sold in the US has nearly quadrupled.

But according to Dr. Gudin, the number of opioid prescriptions has begun to stabilize in the past few years. “The medical community now understands that opioids are not a panacea, and that they come with their own set of potential problems.”

Side effects—including constipation, nausea, dizziness and sweating—are unpleasant and may affect quality of life, but others—including respiratory depression—can lead to accidental overdose and death.

Lethal Chain Reaction, the New Quandry

Historically, opioids (including heroin) have been abused for centuries. Although it can be argued now that public health officials should have recognized the dangers, no one predicted the potential scale of opioid misuse, abuse and addiction.

Lynn Webster, MD, a board-certified anesthesiologist, says 10 to 15percent of the population is “genetically vulnerable to developing an opioid addiction.” The trouble is this: no test can predict who will become addicted. A personal or family history of addiction isn’t an accurate predictor. It merely suggests that the propensity is there.

And it’s not just long-time, frequent users who are at risk. For some, all it takes is one exposure to be “destined for tragedy,” according to Dr. Webster, vice president of Scientific Affairs of PRA Health Sciences and past president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

Opioid abuse is a tremendous public health concern. Part of the country’s opioid problem is the illegal market to which these overprescribed drugs make their way. Patients who develop an addiction after their prescription runs out may turn to illegal avenues, where they can find a plentiful supply.

Physicians must be vigilant bout discussing dangers and evaluating people with pain for signs they could be at risk of addiction. The Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) developed by Dr. Webster is validated, easy to administer and utilized by clinicians in many countries.

When the potential dangers of opioids became known in recent years, physicians had a serious quandary.

“We have an effective treatment option for patients suffering in pain, yet it is associated with serious side effects,” Dr. Gudin says. “Opponents say, ‘They’re too dangerous! Don’t use opioids for anyone.’ And proponents say, ‘Certain patients will be okay on opioids with proper guidance and continued screening/assessment.’

“We have to find a balance, and we have to educate patients, family members and regulators about both the risks and benefits,” Dr.Gudin says. “It’s not all one way or all the other way.”

Speaking of Risks: Have the Conversation

Dr. Gudin is concerned, though, that not enough doctors are talking to patients about risks. “Clinicians who are discussing opioid dangers with their patients are in the minority,” he says.

And some are prescribing too much of a good thing. “Someone may need opioids for a day or two,” Dr. Webster says. “But some doctors will write a prescription for a two-week supply. It becomes too easy for that excess supply to get stolen, given away or traded. This is a supply-side issue. We’ve got to reduce supply.”

The pain epidemic—now also an opioid epidemic—is recognized by the medical community and the government, but patients need to arm themselves with knowledge.

Most patients are familiar with opioid risks and shouldn’t hesitate to bring up concerns or ask questions if the doctor doesn’t do it first.

“Patients have to ask about possible side effects of all therapies—not just about opioids,” Dr. Gudin says. “If you are being prescribed a sedative, for example, you should not combine this with your opioid pain medication or with alcohol. If a particular medicine can cause nausea, ask about the need to take it with food.”

Dr. Webster agrees. “This thought process and these conversations have to happen no matter what the course of treatment,” he says. “We always have to ask the risk/benefit question—whether we’re dealing with opioids, surgery or no treatment at all. And, physicians need to ask themselves: ‘Are there opioid alternatives with less risk?’”

Sometimes the answer is no, which can have a few ramifications. “Most insurance companies refuse to cover any treatment other than opioid therapy,” Dr. Webster says. “So the cautious and compassionate physician is forced to consider opioids.”

He applauds the March announcement by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) on the dangers of opioids, which includes the expanded distribution of naloxone, an opioid antagonist—also known as a reversal agent—and agrees that a federal-level response is what’s needed.

How necessary is this opioid overdose reversal agent? In 2013, 81percent of the nearly 44,000drug overdose deaths in the nation were accidental. More than one-third of them were related to opioid pain relievers.

Do you know how many Americans die each day from an overdose of painkillers? Forty-six. That’s almost two every hour. The risks are deadly…and prevalent.

An Antidote for Opioid Overdose

Opioid overdose victims are usually unconscious and suffering from life-threatening breathing problems that can lead to brain damage—or even death—in minutes.

Naloxone, available to health care providers to reverse opioid over-dose for more than 40years, is now available by prescription and can be administered nasally or injected to neutralize opioids, reversing respiration depression. Advocacy groups, such as the community-based Project Lazarus in North Carolina, offer free kits to patients to promote overdose prevention and opioid safety.

Evzio, the only FDA-approved naloxone for the emergency treatment of opioid overdose, has unique visual and voice instruction (yes, it talks to you!) to guide a layperson through the injection process, making it easy to use with little to no training and without seeing the needle.

The FDA’s deputy director at the Center for Drug Evaluation, Doug Throckmorton, said at the time of EVZIO’s approval, “[EVZIO] enables anyone—even the general public—to inject naloxone from a pre-filled, single-use device into a person who is overdosing.”

People using opioid therapy who are at high risk for overdose (i.e., those on high doses or taking sedatives) can ask their doctors for a co-prescription, covered by most insurance plans, including Medicaid, Medicare, and government insurance plans, including the U.S. Veterans Administration.

In an April 2014 presentationto the House Committee on Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, Nora D. Volkow, MD, of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), applauded the introduction of naloxone to the consumer market. HHS advocates co-prescribing naloxone with opioids. But Dr. Webster says this recommendation “treats a possible consequence of a serious problem but not the problem itself.”

HHS also says more education is needed and that physicians need to make better use of the national prescription registry.

All that’s true, Dr. Webster says. But HHS has been pushing education for two decades. While he doesn’t think they should stop promoting education, he thinks it’s time to lobby Congress to invest money in finding better treatment options. “Research dollars need to be allocated to find opioid alternatives,” he says.

In his open letter to Democratic presidential frontrunner Hillary Clinton, who has acknowledged America’s opioid problem, Dr. Webster wrote, “The opioid crisis is not a black and white issue. Until we stop treating it as such, we will not be able to tackle the problem at its root. Eliminating opioids does not alleviate the problem, end patient suffering or acknowledge what the true issue is. Millions of Americans suffer from chronic pain, but very few have access to multiple options to manage their pain.”

The Future of Opioid Therapy

The opioid epidemic is being taken seriously—by pain management advocates, the government, health care professionals and people who live with pain—but it has several tentacles: over-prescription, overuse, abuse and addiction. While many issues are being addressed by Congress and the FDA*, doctors and the people using opioid therapy can address some concerns at an individual level.

Have a conversation. Everyone needs to talk: doctors and patients, people with pain and their families, patients and caregivers. This is the first and most important step in staying safe with a medication that has the power to do both great good and profound harm. {PP}

PainPathways Magazine

PainPathways is the first, only and ultimate pain magazine. First published in spring 2008, PainPathways is the culmination of the vision of Richard L. Rauck, MD, to provide a shared resource for people living with and caring for others in pain. This quarterly resource not only provides in-depth information on current treatments, therapies and research studies but also connects people who live with pain, both personally and professionally.

View All By PainPathways